New Techniques Help Correct Metal Artifacts in CT Images

Monday, Nov. 28, 2016

More and more patients have metal implants that impede the accurate reading of their CT scans, either by blocking the x-rays or by creating artifacts that obscure the image.

Software is making advances in helping to correct artifact issues caused by the implants, but some correction techniques work better than others, depending on the type of implant and the type of study, according to a research team at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

"Metal artifacts are the most challenging unsolved problem in the 40-year history of CT scans," said Mayo medical physicist Lifeng Yu, PhD.

Artificial joints, amalgam tooth fillings and other metal objects can block the view of the surrounding tissue. The metal itself can also create data inconsistencies from beam hardening, photon starvation, non-linear partial volume effects and beam scattering. These inconsistencies can cause severe streaking and shadow artifacts, making it difficult for radiologists to use the images for diagnosis or to have confidence in their readings.

"When we try to look at structures in the head, a dental amalgam filling can shoot a star artifact that obscures the area," said Mayo medical physicist James Kofler, PhD. "You could tilt the gantry or move the body to keep the amalgam out of your field of view, but that's not always possible."

Removing the artifacts via software is the next best thing, he said.

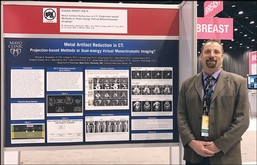

In a poster on display all week at RSNA 2016, Mayo researchers made detailed comparisons of two techniques for correcting images that include metal implants: iterative metal artifact reduction (iMAR), and dual-energy virtual monochromatic imaging. The project also combined the two techniques in processing a third set of images. Most CT manufacturers have introduced some type of metal artifact reduction software that can be used directly from the scanner console.

The team acquired dual-energy CT images of hip, knee, spine and dental implants and also used images taken from patients who had each type of implant. They did post-processing of each set of images using both iMAR and virtual monochromatic imaging.

iMAR identifies the areas that contain metal-contaminated data and either weights those areas less or replaces the data with data from adjacent areas that aren't contaminated. Virtual monochromatic imaging takes advantage of differences in contrast and spectral information between low-energy and high-energy scans, and uses those differences to adjust the weighting factor for areas that have metal artifacts. The latter method is particularly effective in reducing beam hardening artifacts, though scatter and photon starvation artifacts can still remain.

The team's results showed that iMAR did a better job of eliminating artifacts for hip and knee implants, while for dental implants, iMAR actually introduced new artifacts. In that case, dual-energy virtual monochromatic imaging was more effective. For spine implants, the combined method was most effective. However, in all cases, radiologists must keep the original images next to the corrected ones for comparison.

"While the processed images are a great improvement over the originals, the techniques are still not perfect, and the final outcome is case by case," Dr. Yu said.

In their research, Mayo Clinic presenters including Michael R. Bruesewitz, RT(R) (above), compared two techniques for correcting images containing metal artifacts. The poster can be viewed all week from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. in the Physics Community at the Learning Center.

Home

Home Program

Program Exhibitors

Exhibitors My Meeting

My Meeting

Virtual

Virtual Digital Posters

Digital Posters Case of Day

Case of Day